Socrates is credited with saying the "the unexamined life is not worth living;" some wag replied, a lot more recently, that "the unlived life is not worth examining."

Here's a book that helps us to live our lives, and to examine them, or at least to think about them in illuminating and productive ways:

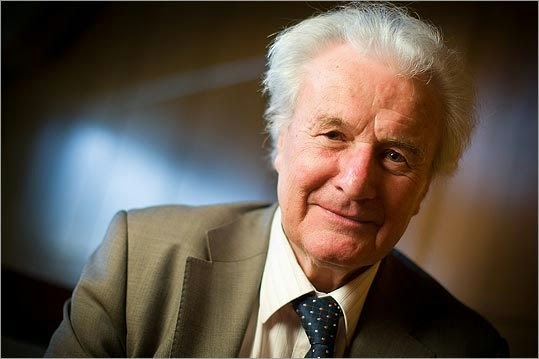

He's a psychoanalyst, and he uses some of his experience with his patients to draw some general ideas about our lives, such as "on secrets," "on not being a couple," "on the recovery of lost feelings."

There is no Freudian jargon, no psychobabble here. He doesn't admonish us or preach to us. He writes clearly, simply even:

"The question is this: can we unhook ourselves by reaching an acceptance of ourselves and our place in time so that we can enjoy our children's pleasures and successes? For at its furthest extreme, envying one's child is a great psychological misfortune, and we stand to lose both our mental equilibrium and our child."

These insights are reached through particular instances, they are never ex cathedra announcements. And Grosz makes plain some of his own uncertainties and difficulties- uses them, even, to add to the evidence underlying what we can learn from him. Like any great doctor, he is a wounded healer.

I found it to be the sort of book that makes you feel a little calmer, more thoughtful, maybe a little larger in the mind, for having read it. I'm certain it will help me relate better, more thoughtfully, to the people I work with.

It's not a long book - about a mid-length train journey's worth of enlightenment - but it's best not hurried.

Tuesday, 27 May 2014

Wednesday, 21 May 2014

A Time Being

There are, according to a classic Zen Buddhist text, a little under six and a half billion moments in one 24-hour day, 65 of them in a finger-snap.

If you snap your fingers and do so 98,463,077 times over the next 24 hours, "you will experience the truly intimate awareness of knowing exactly how you spent every single moment of a single day of your life.

She sat back on her heels and nodded. The thought experiment she proposed was certainly odd, but her point was simple. Everything in the universe is constantly changing, and nothing stays the same, and we must understand how quickly time flows if we are to wake up and truly live our lives.

That's what it means to be a time being, old Jiko told me, and then she snapped her crooked fingers again. And just like that, you die."

That, it seems to me, is why spending at least part of each day in the present moment, not scripting, planning, looking back, anticipating, etc etc etc - is so supremely important. Being a time being is to be less frightened of time passing because time beings are truly living in and with time.

To understand how quickly time flows is to stop being anxious about it. To accept that everything is always changing, at its own speed, is to let go of what cannot, in any case, be held on to.

The Zen text is Shobogenzo, by Dogen. The novel Jiko and the rest of the above quotation is taken from is :

If you snap your fingers and do so 98,463,077 times over the next 24 hours, "you will experience the truly intimate awareness of knowing exactly how you spent every single moment of a single day of your life.

She sat back on her heels and nodded. The thought experiment she proposed was certainly odd, but her point was simple. Everything in the universe is constantly changing, and nothing stays the same, and we must understand how quickly time flows if we are to wake up and truly live our lives.

That's what it means to be a time being, old Jiko told me, and then she snapped her crooked fingers again. And just like that, you die."

That, it seems to me, is why spending at least part of each day in the present moment, not scripting, planning, looking back, anticipating, etc etc etc - is so supremely important. Being a time being is to be less frightened of time passing because time beings are truly living in and with time.

To understand how quickly time flows is to stop being anxious about it. To accept that everything is always changing, at its own speed, is to let go of what cannot, in any case, be held on to.

The Zen text is Shobogenzo, by Dogen. The novel Jiko and the rest of the above quotation is taken from is :

Labels:

being in the present moment,

time,

Zen

Tuesday, 20 May 2014

So what is "natural" about a "natural" burial ground?

There is so much to life that cannot be lived through and by words, and yet words are so important; they are, mostly, where we live, most of our waking hours.

So how we use words, and what we use them to mean, really matters. We mislead ourselves and are easily misled.

"Natural."

What a lot of (fill in your own expletive) this word often covers. E.g: The city is unnatural, the countryside is natural.

Well, this planet peoples, and trees, and lichens, and sturgeons, by which I mean, humans are, obviously, one of the life forms the planet has developed.

We evolved here, just as bower birds and swallows did. Out of raw materials we find in and on the planet, we make very intricate nests where we rest, work, reproduce, etc etc. We put a lot of them together and call it a city.

A city is just as natural as a village - or a swallow's mud nest or a bower-bird's astonishing nest, both of which are made out of raw materials the birds find on the planet. Whether or not our cities upset ecologies and threaten our survival and that of other species is a different issue. It is clearly in our nature to make cities, towns, villages.

Which brings me to "natural" burial sites. People in the funeral business are fond of dividing practice into traditional and ...er... something else. Alternative? I think myself there's only a good funeral, which is one that the family wants and needs, and a bad funeral (which can be bad for many reasons!)

And here we go again - we have "natural" burial grounds, as opposed to "industrial death" crematoria, "gloomy, Victorian" cemeteries, etc. Well, all that is largely a matter of preference, or tatse. Why cloud the decision-making with a spray-on epithet? Why polarise a matter of choice for bereaved people? Enough already with the assumptions.

A "natural" burial ground that I know, and admire in many respects, is simply a cemetery amongst trees, with very small or no headstones. You might think it is more peaceful, or beautiful, or consoling. I might agree, but I don't see what is more "natural" about it than a graveyard.

I don't like shiny granite gravestones either, but they don't make a graveyard less "natural." They make it more obtrusive in the landscape than a "natural" burial ground, which is what I think people often mean when they reach for the handy spray-on word "natural."

As we evolved, we began to put our dead into the ground, with various rituals to give the event meaning, and sometimes we burned them first. All this goes back thousands of years, of course. In that respect, cremating and/or burying a body has become "natural" for our species, as opposed to simply leaving it to decompose where it falls, which is what other animals do.

But if you want to do things differently and need to sell a product - which may well have a powerful and worthwhile belief system behind it - just call it "natural."

I guess the opposite would be an unnatural burial, or funeral. What sort of sense does that make?

This is a lost cause, I know. I wish The Natural Death Centre and the natural burial grounds movement nothing but good, I'm on their side, if sides we must have; but really, we are misleading ourselves, and perhaps even causing unneccessary tensions and anxieties: the title is hogwash!

So how we use words, and what we use them to mean, really matters. We mislead ourselves and are easily misled.

"Natural."

What a lot of (fill in your own expletive) this word often covers. E.g: The city is unnatural, the countryside is natural.

Well, this planet peoples, and trees, and lichens, and sturgeons, by which I mean, humans are, obviously, one of the life forms the planet has developed.

We evolved here, just as bower birds and swallows did. Out of raw materials we find in and on the planet, we make very intricate nests where we rest, work, reproduce, etc etc. We put a lot of them together and call it a city.

A city is just as natural as a village - or a swallow's mud nest or a bower-bird's astonishing nest, both of which are made out of raw materials the birds find on the planet. Whether or not our cities upset ecologies and threaten our survival and that of other species is a different issue. It is clearly in our nature to make cities, towns, villages.

Which brings me to "natural" burial sites. People in the funeral business are fond of dividing practice into traditional and ...er... something else. Alternative? I think myself there's only a good funeral, which is one that the family wants and needs, and a bad funeral (which can be bad for many reasons!)

And here we go again - we have "natural" burial grounds, as opposed to "industrial death" crematoria, "gloomy, Victorian" cemeteries, etc. Well, all that is largely a matter of preference, or tatse. Why cloud the decision-making with a spray-on epithet? Why polarise a matter of choice for bereaved people? Enough already with the assumptions.

A "natural" burial ground that I know, and admire in many respects, is simply a cemetery amongst trees, with very small or no headstones. You might think it is more peaceful, or beautiful, or consoling. I might agree, but I don't see what is more "natural" about it than a graveyard.

I don't like shiny granite gravestones either, but they don't make a graveyard less "natural." They make it more obtrusive in the landscape than a "natural" burial ground, which is what I think people often mean when they reach for the handy spray-on word "natural."

As we evolved, we began to put our dead into the ground, with various rituals to give the event meaning, and sometimes we burned them first. All this goes back thousands of years, of course. In that respect, cremating and/or burying a body has become "natural" for our species, as opposed to simply leaving it to decompose where it falls, which is what other animals do.

But if you want to do things differently and need to sell a product - which may well have a powerful and worthwhile belief system behind it - just call it "natural."

I guess the opposite would be an unnatural burial, or funeral. What sort of sense does that make?

This is a lost cause, I know. I wish The Natural Death Centre and the natural burial grounds movement nothing but good, I'm on their side, if sides we must have; but really, we are misleading ourselves, and perhaps even causing unneccessary tensions and anxieties: the title is hogwash!

Labels:

difficult words,

natrural burial ground,

natural

Monday, 19 May 2014

Fear of flying and Billy Collins

We all know, of course, that flying is statistically, extremely safe. The journey to the airport is potentially much more dangerous than the journey across a continent. So I'm not afraid of flying.

Intuitively, it should be terrifying; it's reason that subdues the fear, I guess. And - mind-numbing, uncomfortable boredom, but that's another topic.

I was relieved to find that I'm not the only one who also feels that underneath the mundane business of Gate no. 14, Flight no. etc, is an extraordinary reality, one that is potentially pretty damned terrifying!

And so characteristic of Billy Collins, the gentle comedy in the last two lines. He is such a wise, humane presence in my life, for which I'm grateful.

Intuitively, it should be terrifying; it's reason that subdues the fear, I guess. And - mind-numbing, uncomfortable boredom, but that's another topic.

I was relieved to find that I'm not the only one who also feels that underneath the mundane business of Gate no. 14, Flight no. etc, is an extraordinary reality, one that is potentially pretty damned terrifying!

And so characteristic of Billy Collins, the gentle comedy in the last two lines. He is such a wise, humane presence in my life, for which I'm grateful.

Passengers

At the gate, I sit in a row of blue seats

with the possible company of my death,

this sprawling miscellany of people—

carry-on bags and paperbacks—

that could be gathered in a flash

into a band of pilgrims on the last open road.

Not that I think

if our plane crumpled into a mountain

we would all ascend together,

holding hands like a ring of skydivers,

into a sudden gasp of brightness,

or that there would be some common place

for us to reunite to jubilize the moment,

some spaceless, pillarless Greece

where we could, at the count of three,

toss our ashes into the sunny air.

It's just that the way that man has his briefcase

so carefully arranged,

the way that girl is cooling her tea,

and the flow of the comb that woman

passes through her daughter's hair ...

and when you consider the altitude,

the secret parts of the engines,

and all the hard water and the deep canyons below ...

well, I just think it would be good if one of us

maybe stood up and said a few words,

or, so as not to involve the police,

at least quietly wrote something down.

with the possible company of my death,

this sprawling miscellany of people—

carry-on bags and paperbacks—

that could be gathered in a flash

into a band of pilgrims on the last open road.

Not that I think

if our plane crumpled into a mountain

we would all ascend together,

holding hands like a ring of skydivers,

into a sudden gasp of brightness,

or that there would be some common place

for us to reunite to jubilize the moment,

some spaceless, pillarless Greece

where we could, at the count of three,

toss our ashes into the sunny air.

It's just that the way that man has his briefcase

so carefully arranged,

the way that girl is cooling her tea,

and the flow of the comb that woman

passes through her daughter's hair ...

and when you consider the altitude,

the secret parts of the engines,

and all the hard water and the deep canyons below ...

well, I just think it would be good if one of us

maybe stood up and said a few words,

or, so as not to involve the police,

at least quietly wrote something down.

Thanks, Mr C.

Labels:

Billy Collins,

fear of death,

fear of flying

Saturday, 17 May 2014

Meditation vs? Action?

Meditation is old and honorable, so why should I

not sit, every morning of my life, on the hillside,

looking into the shining world? Because, properly

attended to, delight, as well as havoc, is suggestion.

Can one be passionate about the just, the

ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit

to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

All summations have a beginning, all effect has a

story, all kindness begins with the sown seed.

Thought buds toward radiance. The gospel of

light is the crossroads of — indolence, or action.

Be ignited, or be gone.

Mary Oliver

But for me, there's an unhelpful opposition here. It's between meditation, and action - being ignited.

I can see no reason why meditation can't be the thing that ignites us, that moves us towards commitment and action. I think it very unlikely that meditating would of itself result in being committed "to no labour in its cause."

Meditation isn't gazing at your navel and letting the world go to hell. Meditation doesn't mean the end of thought, and therefore of "radiance."

It is simply...well, you know what it is. If you don't, let me know and I'll bang on about it for you until you find a true source of wisdom on the subject!

not sit, every morning of my life, on the hillside,

looking into the shining world? Because, properly

attended to, delight, as well as havoc, is suggestion.

Can one be passionate about the just, the

ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit

to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

All summations have a beginning, all effect has a

story, all kindness begins with the sown seed.

Thought buds toward radiance. The gospel of

light is the crossroads of — indolence, or action.

Be ignited, or be gone.

Mary Oliver

But for me, there's an unhelpful opposition here. It's between meditation, and action - being ignited.

I can see no reason why meditation can't be the thing that ignites us, that moves us towards commitment and action. I think it very unlikely that meditating would of itself result in being committed "to no labour in its cause."

Meditation isn't gazing at your navel and letting the world go to hell. Meditation doesn't mean the end of thought, and therefore of "radiance."

It is simply...well, you know what it is. If you don't, let me know and I'll bang on about it for you until you find a true source of wisdom on the subject!

Meditation is old and honorable, so why should I

not sit, every morning of my life, on the hillside,

looking into the shining world? Because, properly

attended to, delight, as well as havoc, is suggestion.

Can one be passionate about the just, the

ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit

to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

All summations have a beginning, all effect has a

story, all kindness begins with the sown seed.

Thought buds toward radiance. The gospel of

light is the crossroads of — indolence, or action.

Be ignited, or be gone.

- See more at: http://www.poetry-chaikhana.com/blog/2012/01/27/mary-oliver-what-i-have-learned-so-far/#sthash.LnXEIk3t.dpuf

not sit, every morning of my life, on the hillside,

looking into the shining world? Because, properly

attended to, delight, as well as havoc, is suggestion.

Can one be passionate about the just, the

ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit

to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

All summations have a beginning, all effect has a

story, all kindness begins with the sown seed.

Thought buds toward radiance. The gospel of

light is the crossroads of — indolence, or action.

Be ignited, or be gone.

- See more at: http://www.poetry-chaikhana.com/blog/2012/01/27/mary-oliver-what-i-have-learned-so-far/#sthash.LnXEIk3t.dpuf

What I Have Learned So Far

by Mary Oliver

Meditation is old and honorable, so why should I

not sit, every morning of my life, on the hillside,

looking into the shining world? Because, properly

attended to, delight, as well as havoc, is suggestion.

Can one be passionate about the just, the

ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit

to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

All summations have a beginning, all effect has a

story, all kindness begins with the sown seed.

Thought buds toward radiance. The gospel of

light is the crossroads of — indolence, or action.

Be ignited, or be gone.

- See more at: http://www.poetry-chaikhana.com/blog/2012/01/27/mary-oliver-what-i-have-learned-so-far/#sthash.LnXEIk3t.dpuf

by Mary Oliver

Meditation is old and honorable, so why should I

not sit, every morning of my life, on the hillside,

looking into the shining world? Because, properly

attended to, delight, as well as havoc, is suggestion.

Can one be passionate about the just, the

ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit

to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

All summations have a beginning, all effect has a

story, all kindness begins with the sown seed.

Thought buds toward radiance. The gospel of

light is the crossroads of — indolence, or action.

Be ignited, or be gone.

- See more at: http://www.poetry-chaikhana.com/blog/2012/01/27/mary-oliver-what-i-have-learned-so-far/#sthash.LnXEIk3t.dpuf

What I Have Learned So Far

by Mary Oliver

Meditation is old and honorable, so why should I

not sit, every morning of my life, on the hillside,

looking into the shining world? Because, properly

attended to, delight, as well as havoc, is suggestion.

Can one be passionate about the just, the

ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit

to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

All summations have a beginning, all effect has a

story, all kindness begins with the sown seed.

Thought buds toward radiance. The gospel of

light is the crossroads of — indolence, or action.

Be ignited, or be gone.

- See more at: http://www.poetry-chaikhana.com/blog/2012/01/27/mary-oliver-what-i-have-learned-so-far/#sthash.LnXEIk3t.dpuf

by Mary Oliver

Meditation is old and honorable, so why should I

not sit, every morning of my life, on the hillside,

looking into the shining world? Because, properly

attended to, delight, as well as havoc, is suggestion.

Can one be passionate about the just, the

ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit

to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

All summations have a beginning, all effect has a

story, all kindness begins with the sown seed.

Thought buds toward radiance. The gospel of

light is the crossroads of — indolence, or action.

Be ignited, or be gone.

- See more at: http://www.poetry-chaikhana.com/blog/2012/01/27/mary-oliver-what-i-have-learned-so-far/#sthash.LnXEIk3t.dpuf

What I Have Learned So Far

by Mary Oliver

Meditation is old and honorable, so why should I

not sit, every morning of my life, on the hillside,

looking into the shining world? Because, properly

attended to, delight, as well as havoc, is suggestion.

Can one be passionate about the just, the

ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit

to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

All summations have a beginning, all effect has a

story, all kindness begins with the sown seed.

Thought buds toward radiance. The gospel of

light is the crossroads of — indolence, or action.

Be ignited, or be gone.

- See more at: http://www.poetry-chaikhana.com/blog/2012/01/27/mary-oliver-what-i-have-learned-so-far/#sthash.LnXEIk3t.dpuf

by Mary Oliver

Meditation is old and honorable, so why should I

not sit, every morning of my life, on the hillside,

looking into the shining world? Because, properly

attended to, delight, as well as havoc, is suggestion.

Can one be passionate about the just, the

ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit

to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

All summations have a beginning, all effect has a

story, all kindness begins with the sown seed.

Thought buds toward radiance. The gospel of

light is the crossroads of — indolence, or action.

Be ignited, or be gone.

- See more at: http://www.poetry-chaikhana.com/blog/2012/01/27/mary-oliver-what-i-have-learned-so-far/#sthash.LnXEIk3t.dpuf

Loons, and us. Your Mary Oliver for the weekend.

Mary Oliver is the poet who currently seems to speak most directly to me of the unity between each of us and the rest of the living world. A loon, BTW, is what we (UK) call a diver (Great Northern, Red-Throated or Black-Throated, over here.) They are not common, very beautiful, and have a most wonderful cry.

Lead

Here is a story

to break your heart.

Are you willing?

This winter

the loons came to our harbor

and died, one by one,

of nothing we could see.

A friend told me

of one on the shore

that lifted its head and opened

the elegant beak and cried out

in the long, sweet savoring of its life

which, if you have heard it,

you know is a sacred thing,

and for which, if you have not heard it,

you had better hurry to where

they still sing.

And, believe me, tell no one

just where that is.

The next morning

this loon, speckled

and iridescent and with a plan

to fly home

to some hidden lake,

was dead on the shore.

I tell you this

to break your heart,

by which I mean only

that it break open and never close again

to the rest of the world.

~ Mary Oliver ~

(New and Slected Poems Volume Two)

I think we need to break open our hearts and never close them again to the rest of the world, as soon as we can, as many of us as possible. To put it crudely - what do we want? More stuff, more closed-off selfishness, or - the rest of the world?

I'd want more loons and less lead.

Lead

Here is a story

to break your heart.

Are you willing?

This winter

the loons came to our harbor

and died, one by one,

of nothing we could see.

A friend told me

of one on the shore

that lifted its head and opened

the elegant beak and cried out

in the long, sweet savoring of its life

which, if you have heard it,

you know is a sacred thing,

and for which, if you have not heard it,

you had better hurry to where

they still sing.

And, believe me, tell no one

just where that is.

The next morning

this loon, speckled

and iridescent and with a plan

to fly home

to some hidden lake,

was dead on the shore.

I tell you this

to break your heart,

by which I mean only

that it break open and never close again

to the rest of the world.

~ Mary Oliver ~

(New and Slected Poems Volume Two)

I think we need to break open our hearts and never close them again to the rest of the world, as soon as we can, as many of us as possible. To put it crudely - what do we want? More stuff, more closed-off selfishness, or - the rest of the world?

I'd want more loons and less lead.

Friday, 16 May 2014

How to make time elastic...

Apart, that is, from having an accident, when as we know, everything slows right down as the car slides towards you, or..well, I expect you know what I mean, no need to scare you. And apart from when you're so over-stressed and hard-pressed that the day just vanishes up its own, er, vanishing point.

After an exhaustive survey of one, I can tell you authoritatively that meditation makes time elastic.

I often take the bus, on a very familiar route. I can meditate, after a fashion, on the bus. I can keep my attention on my body, as it is bounced and jiggled around. (The bus drivers round here don't take prisoners, and the buses are not always of the newest.)

When my attention wanders, I return it gently to my body and its presence, in the seat, in the here and now. My eyes are shut, so people don't try to talk to me. (In fact they probably steer well clear of me: "weirdo alert..")

The other day, I sat with my eyes shut for a few minutes and didn't meditate. I made a guess as to where we were, i.e. how far we'd come, opened my eyes: spot on.

Then I closed my eyes, meditated (as above.) Came back out of meditation, made my guess and: quite wrong. We were substantially further on than I'd thought.

You heard it first here. Meditation elasticises your perception of time.

Don't tell me the bus driver might have gone slower than usual, or the traffic might have been thicker (not much traffic on my route) because it also works during formal meditation. Half an hour, when your back aches and you are trying to stay awake, can seem like a lot more than half an hour.

After an exhaustive survey of one, I can tell you authoritatively that meditation makes time elastic.

I often take the bus, on a very familiar route. I can meditate, after a fashion, on the bus. I can keep my attention on my body, as it is bounced and jiggled around. (The bus drivers round here don't take prisoners, and the buses are not always of the newest.)

When my attention wanders, I return it gently to my body and its presence, in the seat, in the here and now. My eyes are shut, so people don't try to talk to me. (In fact they probably steer well clear of me: "weirdo alert..")

The other day, I sat with my eyes shut for a few minutes and didn't meditate. I made a guess as to where we were, i.e. how far we'd come, opened my eyes: spot on.

Then I closed my eyes, meditated (as above.) Came back out of meditation, made my guess and: quite wrong. We were substantially further on than I'd thought.

You heard it first here. Meditation elasticises your perception of time.

Don't tell me the bus driver might have gone slower than usual, or the traffic might have been thicker (not much traffic on my route) because it also works during formal meditation. Half an hour, when your back aches and you are trying to stay awake, can seem like a lot more than half an hour.

Monday, 12 May 2014

Our 70% useless nation of mortality refusers

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-27369382

Any questions?

OK, then let's get ON with it.

You can't write one of these:

from here:

Neither can you help your family with some idea of your end-of-life and funeral wishes if you have already passed on/croaked/kicked the bucket/fallen off the perch/checked out, etcetcetcetc.

No-one is saying it'll be easy; neither is it easy trying to work out what to do when someone dies, leaving us no idea what he preferred, what he might want, what he thought might help you.

So go on, be an

and get the F on with it! It may make 'em cry, but I reckon you'll feel better afterwards, and so, eventually, will they.

Of course, they may cheer at the prospect of your exit - but let's not go there!

Labels:

death denial,

end of life wishes,

wills

Sunday, 11 May 2014

Timpsons, Undertakers? Why not?

-->

In “The Spectator” last autumn (October 6th,

p. 43), Martin Vander Weyer describes a visit to Timpson’s kiosk for a passport

photo. He writes that the job was done “courteously and with evident pride of

workmanship.”

Whilst he’s waiting, he reads wall posters

that tell him what it’s like to work there; the company supports various

charities, and it holds up “Mr Keen,” “Miss Skilful” and “Mrs Happy” as cartoon

role models. (Don’t sneer, liberalissimos, it works!) Workers – no,

“colleagues” – are entitled to use a selection of holiday homes for free. (I

believe Richer Sounds, also an excellent retailer IMO, has a similar set up)

Timpsons also have a reputation for giving ex-cons a fair crack of the whip.

There are, apparently, 900 Timpson’s kiosks

and it’s still run by the founder’s descendants. It seems “colleagues have the

freedom to do their job the way they choose…no boxes to tick…bosses don’t issue

orders…Head Office is a helpline.” Timpsons call this principle “upside down

management.”

Far be it from me to suggest that certain

large chains of “funeral directors” could learn a great deal from Timpsons,

which is a thriving business. It's not bank-rolled by hedge-fund managers either, as far as we know!

The article ends “In the search for

enlightenment and human kindness in capitalism, the little Timpson kiosk may

have lessons to teach to the giant corporation next door.”

OK, it’s easier selling those excellent

engraved Zippo lighters, or mending your boots, than it is to deal with

grieving families. But I bet Timpsons employees are not harassed by financial targets

and told to upsell the options available to customers.

“Timpsons, Undertakers” – I look forward to

the signs going up.

Meditation transitions - Trigonos harvest part IV

On the beginners' silent retreat weekend at Trigonos, something emerged clearly for me, about movement and transitions. The programme was very effectively structured with alternating half-hour sitting and walking meditations.

I've long known that a simple walking meditation is one of the working methods that suits me best. You place your attention with your feet, feel your balance change and shift as you lean, lift a heel, then the whole foot and very slowly take a pace.

(Use a CD, or better, a teacher, if you want to get into this for the first time - a blogpost won't do it for you!)

You remind yourself that walking has been described as barely-controlled falling over, then you gently return your attention to your feet on and off the ground. I find it a good way to stay in the present, and to return to it as thoughts move in and lead off elsewhere.

Sitting meditation for at least half an hour is the core thing, I think. I accept that "informal practice"(e.g. sitting by a mountain torrent for ten minutes, or looking round the garden first thing in the morning) is not as productive in the long term, though it is valuable, and helps join meditation to the rest of one's life.

At Trigonos, I found the transition between sitting and walking also very helpful. We are creatures of motion and change. It was the transition itself that helped me return to the present moment, as well as the sitting, and the walking.

A group of people doing walking meditation must look very odd to any passer-by - like the start of a science fiction movie - we've been taken over by aliens. Happily, the staff at Trigonos are well used to it, and one or two visitors were tactful enough not to stare or giggle.

I've long known that a simple walking meditation is one of the working methods that suits me best. You place your attention with your feet, feel your balance change and shift as you lean, lift a heel, then the whole foot and very slowly take a pace.

(Use a CD, or better, a teacher, if you want to get into this for the first time - a blogpost won't do it for you!)

You remind yourself that walking has been described as barely-controlled falling over, then you gently return your attention to your feet on and off the ground. I find it a good way to stay in the present, and to return to it as thoughts move in and lead off elsewhere.

Sitting meditation for at least half an hour is the core thing, I think. I accept that "informal practice"(e.g. sitting by a mountain torrent for ten minutes, or looking round the garden first thing in the morning) is not as productive in the long term, though it is valuable, and helps join meditation to the rest of one's life.

At Trigonos, I found the transition between sitting and walking also very helpful. We are creatures of motion and change. It was the transition itself that helped me return to the present moment, as well as the sitting, and the walking.

A group of people doing walking meditation must look very odd to any passer-by - like the start of a science fiction movie - we've been taken over by aliens. Happily, the staff at Trigonos are well used to it, and one or two visitors were tactful enough not to stare or giggle.

Labels:

sitting meditation,

Trigonos,

walking mindfulness

Saturday, 10 May 2014

Past, present and future meditation - Trigonos part III

I would hazard a guess that almost all of us have things about ourselves that we don't like. They may be buried - some people seem remarkably pleased with how they are, at least on the surface - but I reckon they are there. For other people, we can know quite easily what these things are, if we tune in to them. Good friends will sometimes tell us. And there's always guesswork...

Since we're all amateur psychoanalysts these days, sometimes we locate the cause of the bit we don't like in a past pattern of events, experience, trauma. You know the stuff.

The past existed, and a version of the past still exists in our heads, supported of course by documents, photos, music, film clips etc etc.

The future doesn't yet exist, however much we plan and worry about it.

There is a sort of understanding that inhabits you, rather than just staying on nodding terms with your reason. What I understood much more clearly at Trigonos - is this: the past and the future can only exist in the present. There is no-where else they can exist.

How blindingly obvious, you may be thinking. I agree- but how difficult to realise in your mind that it is so, and live in that realisation. It takes, I found, work. Meditation work.

A basic task in meditation is to note and accept what we're thinking, to "be with" it, as the tutors said, without judging it. Just noting it, observing it. It is possible to "be with" the things about ourselves that we don't like, and expand our consciousness around them, broaden our attention.

So it's not, for example, "my disrupted childhood, which has made me so clingy ever since," as an eternally fixed thing about oneself, to regret and dislike. Not a unique, unalterable bad thing, more a pattern of thought. (I made this example up, by the way...)

It's more to do with letting one's attention be with such thoughts whilst we realise they are only thoughts, now, in the present. We can alllow them, note them as part of the present and nothing more.

This work, involving something closer to accepting and letting go, I find so much more useful than trying to...do anything else about negative self-perceptions, really. Striving doesn't help, trying hard ditto.

This stuff - mental states, states of being, kinds of attention - is so hard to write about; I salute those who do.

I understand that neuroscience may support what I'm trying to get at here, because it seems to suggest that we don't recall memories unchanged, pulling them out from a big filing cabinet. We remake them continually, and we change them to fit what we want from them.

So sure, if you get some jolly from thinking you are, say, unalterably clingy, always have been, with a deformed sense of self, then you will. Or you can get doing some meditation work.

Since we're all amateur psychoanalysts these days, sometimes we locate the cause of the bit we don't like in a past pattern of events, experience, trauma. You know the stuff.

The past existed, and a version of the past still exists in our heads, supported of course by documents, photos, music, film clips etc etc.

The future doesn't yet exist, however much we plan and worry about it.

There is a sort of understanding that inhabits you, rather than just staying on nodding terms with your reason. What I understood much more clearly at Trigonos - is this: the past and the future can only exist in the present. There is no-where else they can exist.

How blindingly obvious, you may be thinking. I agree- but how difficult to realise in your mind that it is so, and live in that realisation. It takes, I found, work. Meditation work.

A basic task in meditation is to note and accept what we're thinking, to "be with" it, as the tutors said, without judging it. Just noting it, observing it. It is possible to "be with" the things about ourselves that we don't like, and expand our consciousness around them, broaden our attention.

So it's not, for example, "my disrupted childhood, which has made me so clingy ever since," as an eternally fixed thing about oneself, to regret and dislike. Not a unique, unalterable bad thing, more a pattern of thought. (I made this example up, by the way...)

It's more to do with letting one's attention be with such thoughts whilst we realise they are only thoughts, now, in the present. We can alllow them, note them as part of the present and nothing more.

This work, involving something closer to accepting and letting go, I find so much more useful than trying to...do anything else about negative self-perceptions, really. Striving doesn't help, trying hard ditto.

This stuff - mental states, states of being, kinds of attention - is so hard to write about; I salute those who do.

I understand that neuroscience may support what I'm trying to get at here, because it seems to suggest that we don't recall memories unchanged, pulling them out from a big filing cabinet. We remake them continually, and we change them to fit what we want from them.

So sure, if you get some jolly from thinking you are, say, unalterably clingy, always have been, with a deformed sense of self, then you will. Or you can get doing some meditation work.

Sir Colin Davis and the life after death question

Wonderful interview on BBC4 a few weeks ago with the conductor Sir Colin Davis, not long before he died.

The interviewer asked him about age and death; Davis said he wasn't scared of dying, and the interviewer asked him if he thought there was a life after death. Davis was, I reckon, getting a bit fed up with such questions, so he looked straight at the interviewer and said "I don't know; maybe you can help us out here."

Lovely moment. It showed the ultimate futility of banging away at this question, and the humility of a great man faced with an unanswerable question.

Similarly, a Zen master (look, don't expect references and footnotes from me, OK? I read it somewhere, maybe Brad Warner) was asked by his student "is there a life after death?"

"I don't know," asnwered the ZM.

"I thought you were a Zen Master," said the disappointed student.

"I am, but not a dead one," he snapped.

The interviewer asked him about age and death; Davis said he wasn't scared of dying, and the interviewer asked him if he thought there was a life after death. Davis was, I reckon, getting a bit fed up with such questions, so he looked straight at the interviewer and said "I don't know; maybe you can help us out here."

Lovely moment. It showed the ultimate futility of banging away at this question, and the humility of a great man faced with an unanswerable question.

Similarly, a Zen master (look, don't expect references and footnotes from me, OK? I read it somewhere, maybe Brad Warner) was asked by his student "is there a life after death?"

"I don't know," asnwered the ZM.

"I thought you were a Zen Master," said the disappointed student.

"I am, but not a dead one," he snapped.

Tuesday, 6 May 2014

Death and Billy Collins: two of his poems

We didn't have any Billy C at Trigonos, but we could well have done - e.g. "Picnic, Lightning," which is very much about the present moment. On that slender excuse, I give you two poems you may or may not know, about death, just to make the point that Collins spends much attention on being right in the present moment of his life, the "drop running along the green leaf." Or as the New Yorker critic put it once, "What Collins does best is turn an apparently simple phrase into a numinous moment." Quite.

No Things

This love for the petty things,

part natural from the slow eye of childhood,

part literary affectation,

this attention to the morning flower

and later in the day to a fly

strolling along the rim of a wineglass -

are we just avoiding the one true destiny,

when we do that? Averting our eyes from

Philip Larkin who waits for us in an undertaker's coat?

The leafless branches against the sky

will not save anyone from the infinity of death,

nor will the sugar bowl or the sugar spoon on the table.

So why bother with the checkerboard lighthouse?

Why waste time on the sparrow,

or the wild flowers along the roadside

when we should be all alone in our rooms

throwing ourselves against the wall of life

and the opposite wall of death,

the door locked behind us

as we hurl ourselves at the question of meaning,

and the enigma of our origins?

What good is the firefly,

the drop running along the green leaf,

or even the bar of soap spinning around the bathtub

when ultimately we are meant to be

banging away on the mystery

as hard as we can and to hell with the neighbours?

banging away on nothingness itself,

some with their foreheads,

others with the maul of sense, the raised jawbone of poetry.

and

My Number

Is Death miles away from this house,

reaching for a widow in Cincinnati

or breathing down the neck of a lost hiker

in British Columbia?

Is he too busy making arrangements,

tampering with air brakes,

scattering cancer cells like seeds,

loosening the wooden beams of roller-coasters

to bother with my hidden cottage

that visitors find so hard to find?

Or is he stepping from a black car

parked at the dark end of the lane,

shaking open the familiar cloak,

its hood raised like the head of a crow

and removing the scythe from the trunk?

Did you have any trouble with the directions?

I will ask, as I start talking my way out of this.

(He also has a lovely sly sense of humour.)

No Things

This love for the petty things,

part natural from the slow eye of childhood,

part literary affectation,

this attention to the morning flower

and later in the day to a fly

strolling along the rim of a wineglass -

are we just avoiding the one true destiny,

when we do that? Averting our eyes from

Philip Larkin who waits for us in an undertaker's coat?

The leafless branches against the sky

will not save anyone from the infinity of death,

nor will the sugar bowl or the sugar spoon on the table.

So why bother with the checkerboard lighthouse?

Why waste time on the sparrow,

or the wild flowers along the roadside

when we should be all alone in our rooms

throwing ourselves against the wall of life

and the opposite wall of death,

the door locked behind us

as we hurl ourselves at the question of meaning,

and the enigma of our origins?

What good is the firefly,

the drop running along the green leaf,

or even the bar of soap spinning around the bathtub

when ultimately we are meant to be

banging away on the mystery

as hard as we can and to hell with the neighbours?

banging away on nothingness itself,

some with their foreheads,

others with the maul of sense, the raised jawbone of poetry.

and

My Number

Is Death miles away from this house,

reaching for a widow in Cincinnati

or breathing down the neck of a lost hiker

in British Columbia?

Is he too busy making arrangements,

tampering with air brakes,

scattering cancer cells like seeds,

loosening the wooden beams of roller-coasters

to bother with my hidden cottage

that visitors find so hard to find?

Or is he stepping from a black car

parked at the dark end of the lane,

shaking open the familiar cloak,

its hood raised like the head of a crow

and removing the scythe from the trunk?

Did you have any trouble with the directions?

I will ask, as I start talking my way out of this.

(He also has a lovely sly sense of humour.)

Labels:

Billy Collins,

death,

the grim reaper,

the present moment

Monday, 5 May 2014

Simon Russell Beale's King Lear, and mindfulness: Trigonos experience part II

The evening before arriving at Trigonos, I watched the live telecast from the National Theatre's "King Lear," with Simon Russell Beale as he who had to be mad before he could be sane.

I've seen a few in me time, taught it, thought about it. I think this production is the best I've seen, a huge achievement, taking in the vast range of the play. Salute the cast and their director for the power and scope of the journey they take us on.

"He hath ever but slenderly known himself," says Regan, in one of those withering little comments from the heart of domestic as well as political resentments. Mindfulness should help us know ourselves, I thought later.

But who does?

We were warned gently, at Trigonos, that extended periods of meditation could bring up powerful feelings unexpectedly.

I'm sitting calmly in meditation, after a discussion in which someone in the group mentions some real pain she has gone through and is going through. From nowhere - bang! - comes the line from the depth of suffering in "King Lear."

"I know thee well enough; thy name is Gloucester."

My eyes fill up and spill over. All the grief we carry for each other, all the cruel arbitrariness of suffering and death.

Where did this surge of grief come from, in this peaceful, beautiful place, light years from the drama of a mad old king and a blinded, deluded Earl?

"Thou must be patient; we came crying hither..."

For the rest of the day, those two ruined old heads leaning against each other won't leave me alone.

"I know thee well enough; thy name is Gloucester."

Don't tell me "it's only a play." It's a touch-stone of our humanity, it's the depths, and the heights in Cordelia's instantaneous forgiveness: "No cause, no cause."

If meditation is to do its job for us, it's hard work, really hard work sometimes.

I've seen a few in me time, taught it, thought about it. I think this production is the best I've seen, a huge achievement, taking in the vast range of the play. Salute the cast and their director for the power and scope of the journey they take us on.

"He hath ever but slenderly known himself," says Regan, in one of those withering little comments from the heart of domestic as well as political resentments. Mindfulness should help us know ourselves, I thought later.

But who does?

We were warned gently, at Trigonos, that extended periods of meditation could bring up powerful feelings unexpectedly.

I'm sitting calmly in meditation, after a discussion in which someone in the group mentions some real pain she has gone through and is going through. From nowhere - bang! - comes the line from the depth of suffering in "King Lear."

"I know thee well enough; thy name is Gloucester."

My eyes fill up and spill over. All the grief we carry for each other, all the cruel arbitrariness of suffering and death.

Where did this surge of grief come from, in this peaceful, beautiful place, light years from the drama of a mad old king and a blinded, deluded Earl?

"Thou must be patient; we came crying hither..."

For the rest of the day, those two ruined old heads leaning against each other won't leave me alone.

"I know thee well enough; thy name is Gloucester."

Don't tell me "it's only a play." It's a touch-stone of our humanity, it's the depths, and the heights in Cordelia's instantaneous forgiveness: "No cause, no cause."

If meditation is to do its job for us, it's hard work, really hard work sometimes.

Labels:

King Lear,

meditation and suffering,

Trigonos

Happiness - it'll jump you, if you can let it.

Coconut

-->

From Bending the Notes (Main Street Rag, 2008) by

Paul Hostovsky

-->

Bear with me I

want to tell you

something about

happiness

it’s hard to get at

but the thing is

I wasn’t looking

I was looking

somewhere else

when my son found it

in the fruit section

and came running

holding it out

in his small hands

asking me what

it was and could we

keep it it only

cost 99 cents

hairy and brown

hard as a rock

and something swishing

around inside

and what on earth

and where on earth

and this was happiness

this little ball

of interest beating

inside his chest

this interestedness

beaming out

from his face pleading

happiness

and because I wasn’t

happy I said

to put it back

because I didn’t want it

because we didn’t need it

and because he was happy

he started to cry

right there in aisle

five so when we

got it home we

put it in the middle

of the kitchen table

and sat on either

side of it and began

to consider how

to get inside of it.

want to tell you

something about

happiness

it’s hard to get at

but the thing is

I wasn’t looking

I was looking

somewhere else

when my son found it

in the fruit section

and came running

holding it out

in his small hands

asking me what

it was and could we

keep it it only

cost 99 cents

hairy and brown

hard as a rock

and something swishing

around inside

and what on earth

and where on earth

and this was happiness

this little ball

of interest beating

inside his chest

this interestedness

beaming out

from his face pleading

happiness

and because I wasn’t

happy I said

to put it back

because I didn’t want it

because we didn’t need it

and because he was happy

he started to cry

right there in aisle

five so when we

got it home we

put it in the middle

of the kitchen table

and sat on either

side of it and began

to consider how

to get inside of it.

From Bending the Notes (Main Street Rag, 2008) by

Paul Hostovsky

Mindfulness retreat at Trigonos

This is Trigonos:

a study/retreat centre in Nantlle, Snowdonia. It's a wonderful place, well suited to a weekend silent retreat for people who have already taken the eight-week evening class in mindfulness meditation, or one of its variants.

I want to try to explain some of the things I have taken from the experience, in the hope that some of it may be useful to my legions of reader out there.

Trigonos is in a very beautiful dramatic setting, and these pics only give you an idea, a sketch; they can't capture the particular atmosphere and ethos of the place. This is the view from the house down to the lake:

It is a place of calm, although silence and meditation can release powerful and unexpected feelings, of which more, you'll be delighted to hear, later. But Trigonos is a natural choice for a place to be, for at least some of the time, in the present moment.

One point for now: it was a non-speaking 36 hours, rather than a silent one, since one of the techniques is to place your attention in the ears, as it were- simply listening and accepting all you can hear, whether it's the birdsong outside (loved the honk from the geese and the raven's croak, as well as the blackbirds) or a distant dog, or a chainsaw, or the tummy of your meditation neighbour who is overdue for some lunch.

Sarah Maitland's "The Book of Silence" is as much about solitude as silence, I felt when I read it. There is nothing lonely, nothing solitary, about communal silence, non-speaking, whether it's in the meditation gallery or during meal-times. It's very powerful.

More on this soon.

a study/retreat centre in Nantlle, Snowdonia. It's a wonderful place, well suited to a weekend silent retreat for people who have already taken the eight-week evening class in mindfulness meditation, or one of its variants.

I want to try to explain some of the things I have taken from the experience, in the hope that some of it may be useful to my legions of reader out there.

Trigonos is in a very beautiful dramatic setting, and these pics only give you an idea, a sketch; they can't capture the particular atmosphere and ethos of the place. This is the view from the house down to the lake:

It is a place of calm, although silence and meditation can release powerful and unexpected feelings, of which more, you'll be delighted to hear, later. But Trigonos is a natural choice for a place to be, for at least some of the time, in the present moment.

One point for now: it was a non-speaking 36 hours, rather than a silent one, since one of the techniques is to place your attention in the ears, as it were- simply listening and accepting all you can hear, whether it's the birdsong outside (loved the honk from the geese and the raven's croak, as well as the blackbirds) or a distant dog, or a chainsaw, or the tummy of your meditation neighbour who is overdue for some lunch.

Sarah Maitland's "The Book of Silence" is as much about solitude as silence, I felt when I read it. There is nothing lonely, nothing solitary, about communal silence, non-speaking, whether it's in the meditation gallery or during meal-times. It's very powerful.

Labels:

meditation,

mindfulness,

the present moment,

Trigonos

Thursday, 1 May 2014

Funeral judgements: the story of a life

"Some day I'm gonna write, the story of my life," sang Michael Hollliday way back in my childhood (OK OK, youth) - but usually, the life story for a funeral is written by family+celebrant.

There's been useful discussion on the Good Funeral Guide website about the relative value of the potted biography "sandwich" in the middle of a ceremony.

Leaving that question aside for the moment, and accepting if you will that a potted biography is exactly what some families want, another and possibly more important issue arises.

Judgements.

Why do we seem to feel the need to sum up a life and pass judgement on it? "He never lost his temper." Really? "He would do anything for anyone." Maybe. "Everyone says he was a true gentleman." Well they would, wouldn't they - he's just died, and they liked him.

I'm not being cynical. The torrent of unqualified praise that falls on us when someone has just died is an expression of sorrow and compassion, of course. But the only way to set the balance straight and strive for a more balanced, seemingly accurate picture would be to talk about the less angelic side of someone's nature.

"He was usually very even-tempered, but would occasionally throw things around the room." "He was a true gentleman, except for the time he got drunk at Christmas and made a pass at Auntie Ethel. Well, and the time....." H'mmm. Tricky. Could make 'em laugh; could go horribly wrong. "Warts and all" is not usually what people want at a funeral, I think, though it might be what the old rogue would have enjoyed himself.

Occasionally, you get a lovely useable judgement, such as "he was a grumpy old sod, but he was my grumpy old sod. I miss him and I'm proud of him." Poignant, rings true.

So I think the problem is not the biography as such, it's the illusion that we can make useful summary statements in judgement upon someone's character.

Who are we to pronounce judgement upon the flickering, shimmering transience of a personality? The imperfect wonders of a human life?

How much better to have people tell us, directly or via the celebrant, what the person meant to them. How much better to have anecdotes and stories that illustrate some well-known characteristics; they bring about the smiles of recognition and affectionate grief, they mean much more than generalised and abstract judgements.

Sometimes events in someone's life need to be given straight. "She was a radio operator in France for the SOE during the last year of the war and had to escape..." If there are people who didn't know that in the congregation, they need to. "He worked for twenty years as a volunteer for The Samaritans, and hardly mentioned it to anyone." Ditto. Statements can be made to speak for themselves, even at the more domestic level. "He belonged to the RSPB most of his life, and raised money for them when he could."

Let's accept the limits of human judgement and not encumber a funeral with verdicts.

Here's Michael Holliday, for nostalgia freaks.

There's been useful discussion on the Good Funeral Guide website about the relative value of the potted biography "sandwich" in the middle of a ceremony.

Leaving that question aside for the moment, and accepting if you will that a potted biography is exactly what some families want, another and possibly more important issue arises.

Judgements.

Why do we seem to feel the need to sum up a life and pass judgement on it? "He never lost his temper." Really? "He would do anything for anyone." Maybe. "Everyone says he was a true gentleman." Well they would, wouldn't they - he's just died, and they liked him.

I'm not being cynical. The torrent of unqualified praise that falls on us when someone has just died is an expression of sorrow and compassion, of course. But the only way to set the balance straight and strive for a more balanced, seemingly accurate picture would be to talk about the less angelic side of someone's nature.

"He was usually very even-tempered, but would occasionally throw things around the room." "He was a true gentleman, except for the time he got drunk at Christmas and made a pass at Auntie Ethel. Well, and the time....." H'mmm. Tricky. Could make 'em laugh; could go horribly wrong. "Warts and all" is not usually what people want at a funeral, I think, though it might be what the old rogue would have enjoyed himself.

Occasionally, you get a lovely useable judgement, such as "he was a grumpy old sod, but he was my grumpy old sod. I miss him and I'm proud of him." Poignant, rings true.

So I think the problem is not the biography as such, it's the illusion that we can make useful summary statements in judgement upon someone's character.

Who are we to pronounce judgement upon the flickering, shimmering transience of a personality? The imperfect wonders of a human life?

How much better to have people tell us, directly or via the celebrant, what the person meant to them. How much better to have anecdotes and stories that illustrate some well-known characteristics; they bring about the smiles of recognition and affectionate grief, they mean much more than generalised and abstract judgements.

Sometimes events in someone's life need to be given straight. "She was a radio operator in France for the SOE during the last year of the war and had to escape..." If there are people who didn't know that in the congregation, they need to. "He worked for twenty years as a volunteer for The Samaritans, and hardly mentioned it to anyone." Ditto. Statements can be made to speak for themselves, even at the more domestic level. "He belonged to the RSPB most of his life, and raised money for them when he could."

Let's accept the limits of human judgement and not encumber a funeral with verdicts.

Here's Michael Holliday, for nostalgia freaks.

Labels:

funeral judgements,

life stories

Kate Tempest and kintsugi

Extract from "Brand New Ancients:"

In the old days,

the myths were the stories we used to explain ourselves

but how can we explain

the way we hate ourselves?

The things we’ve made ourselves into,

the way we break ourselves in two,

the way we overcomplicate ourselves?

But we are still mythical.

We are still permanently trapped

somewhere between the heroic and the pitiful.

We are still Godly,

that’s what's made us so monstrous.

It just feels like we’ve forgotten

that we’re much more

than the sum of the things that belong to us.

Every single person has a purpose in them burning.

Look again.

Allow yourself to see them.

Millions of characters

Each with their own epic narratives

Singing, ‘it’s hard to be an angel

Until you’ve been a demon’.

We are perfect because of our imperfections,

We must stay hopeful,

We must be patient

with thanks to Kate Tempest & co.

I think there's a lot in this. "We are perfect because of our imperfections" - kintsugi.

And we do, each of us, have a narrative, epic perhaps to each of us. If we "look again," we can allow ourselves to see them. Working with the families of people who have just died - that gives us a privileged view of each personal epic.

And we are so much more than the sum of the stuff we own; as consumer capitalism cranks up into overdrive, it gets harder and harder to realize this, harder to see the unique story under the stuff s/he owns.

And each of us is both angel and demon. If we externalise the demon and project it onto others, we release true evil into the world.

You can see Kate Tempest at work on YouTube, where she will bring the above printed words to life, and some.

Is she a descendant of William Blake, I wonder?

In the old days,

the myths were the stories we used to explain ourselves

but how can we explain

the way we hate ourselves?

The things we’ve made ourselves into,

the way we break ourselves in two,

the way we overcomplicate ourselves?

But we are still mythical.

We are still permanently trapped

somewhere between the heroic and the pitiful.

We are still Godly,

that’s what's made us so monstrous.

It just feels like we’ve forgotten

that we’re much more

than the sum of the things that belong to us.

Every single person has a purpose in them burning.

Look again.

Allow yourself to see them.

Millions of characters

Each with their own epic narratives

Singing, ‘it’s hard to be an angel

Until you’ve been a demon’.

We are perfect because of our imperfections,

We must stay hopeful,

We must be patient

with thanks to Kate Tempest & co.

I think there's a lot in this. "We are perfect because of our imperfections" - kintsugi.

And we do, each of us, have a narrative, epic perhaps to each of us. If we "look again," we can allow ourselves to see them. Working with the families of people who have just died - that gives us a privileged view of each personal epic.

And we are so much more than the sum of the stuff we own; as consumer capitalism cranks up into overdrive, it gets harder and harder to realize this, harder to see the unique story under the stuff s/he owns.

And each of us is both angel and demon. If we externalise the demon and project it onto others, we release true evil into the world.

You can see Kate Tempest at work on YouTube, where she will bring the above printed words to life, and some.

Is she a descendant of William Blake, I wonder?

Labels:

kintsugi,

materialism,

the problem of evil

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)